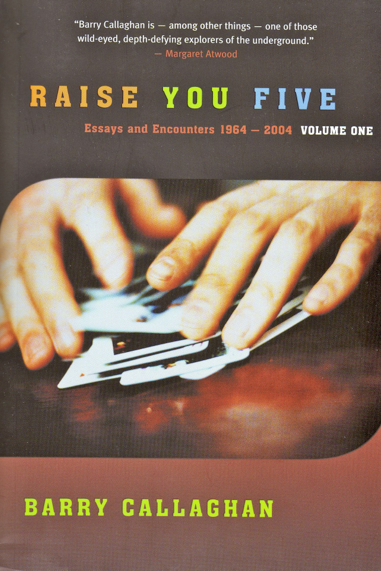

BARRY CALLAGHAN

man of letters

BARRY CALLAGHAN

man of letters

MEDIA: JOURNALIST

PONCE IN PUERTO RICO

Ponce de León was a plunger, a man who had put his dream on the line and had called out, “Raise you five,” a man who’d come clanking across the sea in an iron suit, a soldier who had scoured all the old scouting reports and maps of islands, tracing little zigzag lines with his long forefinger, zigzag rivers that he believed were lined with gold pebbles. He was a scoundrel but he was a scoundrel in love with the hills of his illusions. He’d gone off over an ocean that practical men of good sense and fear had insisted was flat. He’d gone off into the abyss of the unknown believing that the abyss is always filled with possibilities, that catastrophe is better by far than a false success.

Before he died, he’d been in Cuba and he’d found Bimini and he was part of the map-makers’ news. Balboa was on a peak in Darién, de Soto was not yet dead at the Arkansas, Cortés was in Vera Cruz pretending he was a plumed serpent, and Pizarro was on the road to Machu Picchu. Ponce had surrounded himself with tattooed ladies, but even love in the afternoon had loomed up at last as too boring for him, boredom becoming a constant ache in the back of his brain, and so he had hauled anchor for the green hills one hundred and fifty leagues east, Boriquén, the port called Rico. Runners across the water had told him about gold and rivers where handfuls of gold pebbles lay in shallow water just for the taking, and within the week he had rowed in on the breakers on the north shore and announced that among the conquistadors he was the adelantado, the front-runner. He’d also told the gawking Indians that he was the son of the sun, and he set up a sundial so

that they would know at exactly what time they were going to die.

The Indians thought Ponce, with his flesh the colour of the ash of dead fires, was supernatural, but then a chief, a man called Brayoan, ambushed one of Ponce’s scouts and held him head-first under the magic water. He drowned, and since that drowning seemed easy enough, the Indians killed six more men. But the white scouts kept coming in their leather and iron and the Indians concluded that they could only be coming back from the dead, resurrected, just as Ponce had said their magic lord had been resurrected, the lord they called Jesus. In two years Ponce had conquered the island. His men, carrying the true cross, had become rich; thirty-four years later, when Carlos V abolished slavery in the gold mines, some forty thousand Taínos were dead. They did not come back from the dead.

It happened that Ponce had a close friend, Don Cristobal de Sotomayor, who – as he was being hung up by the heels by the Indians on the road to San Juan – made a last request, and that request was that Ponce should look after his ward, a child countess back in Spain. Ponce, whose skin by this time had taken on the putty hue of coming old age, with a liverish blue under the eyes, was wealthy and respected, and tired. He sailed for home. But when he saw his sloe-eyed, sprightly, sharp-minded ward, who soon would come into one of the largest dowries in Spain, he first licked his dry lips and then he fell in love. He picked up a mirror of highly polished gold, winced, and wanted only one thing. He wanted his youth. Because cannibals had told him that there was a miraculous fountain of youth in the islands, he decided to gamble everything. Possibilities lurched in his mind; he packed up, smiling, full of hope, and set out to discover the front porch of the dead, Miami Beach.

In that year, 1521, the year Cortés took Tenochititlan apart, Ponce saw Pascua Florida for the first time, a flower-covered land, and he went ashore with three hundred and seventy men, and soon he was rooting around in the rivers and streams for his youth. He let

youth. He let water from a phosphorous bay run down his outstretched arms, droplets of light. He called out the name of the child countess. Indians who wore their hair tufted and cut like acorn tops stood silently by on the banks of the rivers, some hunched forward inside stag skins, wagging their antlers, and then the stags attacked. They hacked the white men to pieces.

An arrow hit Ponce in the thigh, close to the femoral artery. The arrow splintered in the bone. Ponce, weakening from loss of blood, cried, “Jesus, I couldn’t help myself, help me now.” He waited for a little help and got none and, watching his blood spill away, he wept because he’d only wanted to be loved, to embrace life, to be the adelantado. He knew it was for the last time but anyway he called out, “Raise you five.”

Now he stands at the centre of a square in old San Juan amidst dwarf trees and wrought-iron benches. He stands on a high stone pedestal, Ponce de León the plunger, in his iron suit with feathers in his hat. His one hand on his hip, the other is pointing off into the hills, his bottle green body is made out of discarded cannon melted down and at his throat he is dressed with a scorpion’s tail, he is still invincible at ballroom dancing, and is eager to sup on alligator wine and a little serpent’s fat, and learned in magic, he woos a woman . . .

Toronto Life, 1978